Support from Education Forward DC and the National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships

The DC Education Research Collaborative’s mission is to guide and support the District’s education community in their work. As a part of the city’s robust research ecosystem, conducting original research is just one of the ways we provide information to educators and decision makers as they work on behalf of DC’s students. Another way is by facilitating others as they undertake their own projects, especially in participant-research that is designed and led by practitioners, community members, and, in this important case, students.

In December 2022, leaders at the Columbia Heights Educational Campus (CHEC) approached Collaborative researchers. CHEC is a DCPS school enrolling 1,520 students in grades 6-12. Students represent 67 countries and 41 home languages, and nearly 99% of students are Black and/or Hispanic. At the start of the 2022-23 school year, CHEC set a strategic goal of increasing student voice, engagement and empowerment, and the school adopted a student-centered design thinking and research process. In design thinking, the people affected by decisions are the ones who make the decisions, using research and data to guide them.

From the Collaborative, CHEC was seeking an advisor for the students’ design thinking research. We agreed and adopted a youth participatory action research (YPAR) framework to guide us. “Student participation” is often given superficial treatment in research, perhaps by including students as a data source or involving them as research assistants. In youth participatory action research, however, young people are trained to conduct systematic research, from start to finish, to improve their lives, their communities, and the institutions intended to serve them. Much like design thinking, in the YPAR model the students gather data from their peers about opportunities for change and improvement at their school, define the opportunity they want to tackle, conceive of possible solutions, choose a course of action and plan for implementation, and make adjustments based on the results. Along the way, researchers and educators build students’ capacity, support putting their plan into action, and commit to centering the students’ expertise and choices.

Researcher Reflections

The work with CHEC allowed us to move away from what we normally do as researchers and set the standard for how the Collaborative will engage with the target community on every project. We let the students set the direction, tell us about their goals, and what they wanted our help with. On other projects, I spend my time conducting statistical analyses or writing up findings; I mostly engage with people internal to my own organization. With this project, a large part of our work involves going to the school during the school day and getting to interact with the students in their daily environment. This allows us to more clearly see the problems they are talking about and how they would like to fix them. It also creates an active partnership with CHEC where we are able to set weekly objectives, check-in about them, and adjust as needed.

When we joined the CHEC team, they had already gathered information about the opportunities for improvement. Opportunities ranged from tardiness to vandalism in the restrooms, from increasing student engagement post-Covid to giving students more choice in their academic programs of study.

Our particular project with the CHEC students is around food equity. The group wanted to improve learning, motivation, and school culture by making sure students weren’t hungry. They maintained this wasn’t simply an issue of ensuring adequate calories but also improving the overall quality of the school food, providing healthy and culturally diverse meals for students in a fun and engaging environment, and giving students the autonomy and ability to eat what, when, and where they needed to. Success would be a major step toward their overall goal for the school: to make CHEC a place where adults listen to students, where students’ cultures are valued, and where students are heard, cared for, and can make decisions for themselves.

Year 1

At our first meeting with the CHEC students, we weren’t sure what to expect. Where were the students in their design thinking process? What did the students already know about research? We listened carefully as the students outlined the work they had done so far: the issue they identified, who they talked to about the issue, and what solutions they wanted to implement. Our job was to help them put the plan into action, study the impact they had, and aligned their work to the scientific method. We also prepared students to present these findings.

Over the coming months, we met with students to discuss the results of their interviews and the surveys they conducted around the school to assess student needs and the changes students would like to see in the cafeteria and in their school. School leaders facilitated meetings with the food supplier, set up taste-test focus groups, and brought them to speak with district and city leaders. Together we designed new data collection instruments and data analysis strategies to see whether the changes had met their goals.

The data gathered through surveys and observations showed students weren't eating school food because it wasn't:

- Appealing

- Sanitary

- Fresh

- Culturally diverse

- lnviting

During the research process, we also learned that:

- Over 60% of students didn't eat food provided by the school cafeteria

- There is a limited budget for food and there are restrictions due to nutritional guidelines

- There is poor

communication between the food supplier and the district

The solution we designed:

- We would work with the food supplier to make menu changes that offered students food they wanted, that would also fit within the nutritional requirement and budget.

Year 1 focused on the main avenue of food distribution for the students: the cafeteria. The team learned about student preferences and the litany of rules, regulations, and requirements that went into food service. Their chosen approach was to work with the existing supplier to make changes to the school’s breakfast and lunch menus .

What solution was implemented?

We negotiated with the food supplier and, in response to student feedback, the supplier launched the THRIVE program on February 20, 2023. The THRIVE program:

- Increased the number of menu options

- Brought back the salad bar

- Used better quality ingredients

- Included culturally relevant dishes

- Enhanced the dining experience with wall art, banners, and sign holders

- Provided trainings for the school Food Service Staff on food preparation and presentation

- Published weekly breakfast and lunch menus

What changed as a result?

- After THRIVE, lunch participation rose from a low of 43% to consistently over 60%

- More students are eating in the cafeteria and fewer are wandering in the hallways during lunch.

Even students who bring their lunch from home are eating in the cafeteria. - DC City Council did not automatically renew food vendor contract but instead created a probationary period

In the early 2023, our team was accepted to present at the 2023 American Educational Research Association (AERA) annual conference in Chicago, IL, as part of AERA’s first-ever “Youth Teams in Education Research Program” program. We prepared and practiced a presentation that identified the opportunities for research, data and methods, solutions, and impact. We accompanied five students and one teacher to Chicago where our team participated in a three-day workshop with nine other teams from around the country and shared our work with university professors, education scholars, superintendents, principals, teachers, and advocates. Over the course of the conference, students spoke with pride about not only the changes implemented at their school, but at the way they, and not the adults, were the drivers of the work.

To close out the 2022-23 school year, we co-designed and administered a school-wide survey to gauge students’ food experiences over the school year, to see whether the THRIVE program was having the outcomes we intended, and to understand what else they might want. We used the data to set the team’s long-term goals for the food equity project and to identify what other research needed to be done to achieve these goals.

Year 2

The opening of the 2023-2024 school year brought in new and returning students to the food equity group. (The new students told us they joined us because they wanted to be a part of our important, empowering work…but we know the breakfast or snacks we brought the team each week probably convinced them too!)

The data we gathered through surveys and observations showed students weren't eating school food because:

- It wasn't available when they could or wanted to access it

- They couldn't eat it where they wanted to--many students preferred socializing, playing sports, clubs, and other non-cafeteria activities

- Despite positive changes from the supplier, it was still "cafeteria food"

During the research process, we also learned that:

- Food creates a sense of community at school, even (or especially) if it wasn't cafeteria food

- The supplier was limited by what they could provide and where

- We were not allowed to offer our own food at the same time/place as school breakfast and lunch

The solution we designed:

- We would implement a snack distribution program during the school day, first as a pilot to collect data and learn from implementation.

As before, we started by identifying the opportunities and goals for the year. Survey and observation data told the student team that the THRIVE program had improved the food quality and cafeteria environment. While there was still work to be done with school breakfast and lunch, the team (both students and educators) believed that areas for further improvement could be handled directly with the food supplier and that there were other opportunities that demanded the team’s attention this year: specifically, they realized that to meet their goals of students feeling fed and cared for, they needed another avenue besides the cafeteria.

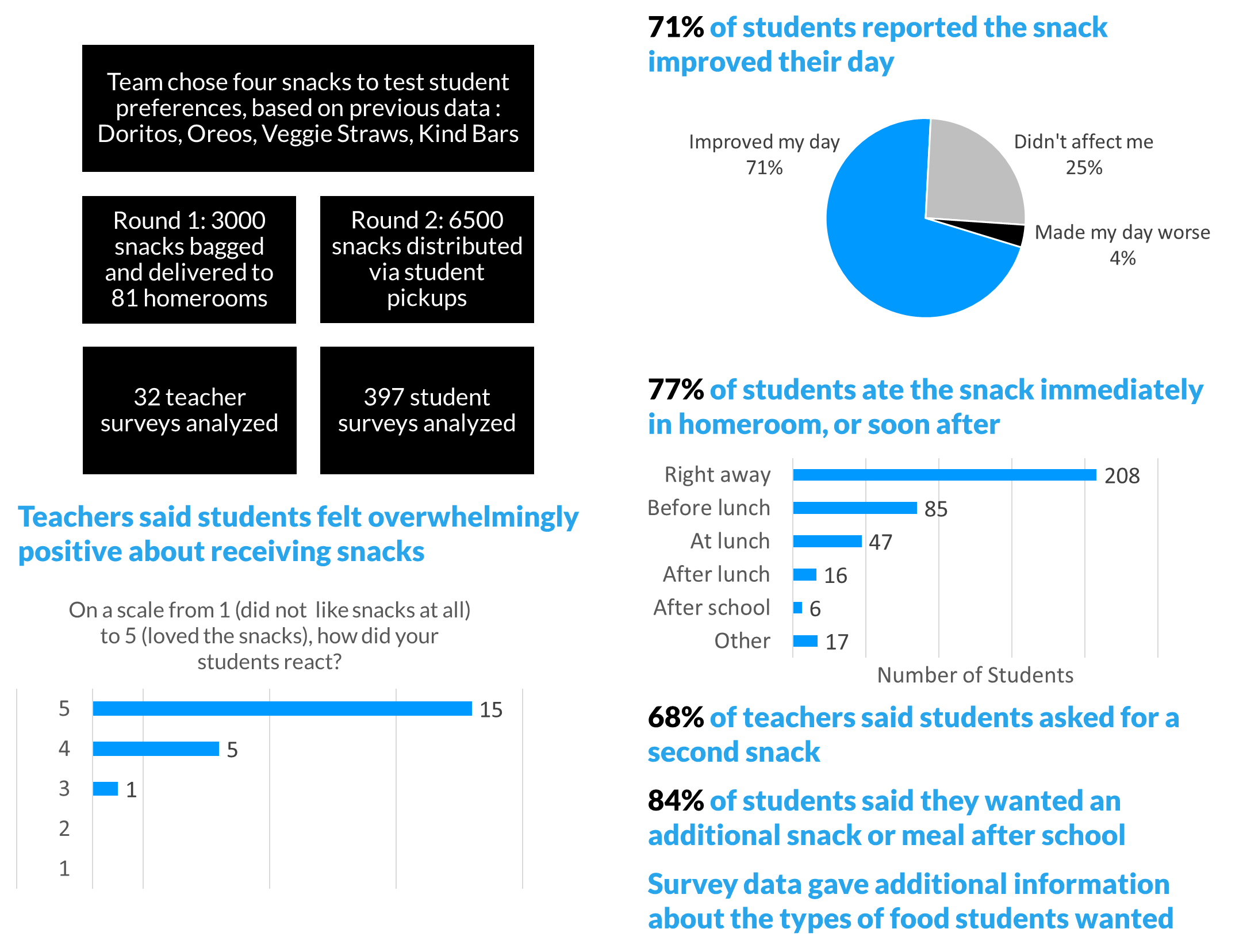

Through the school-wide student survey, the student researchers learned that their peers could benefit from a filling snack during the day to tide them over between the start of school and lunch or lunch and the end of school. They picked out snacks to test with the student body, planned for the weekly distribution of these snacks, and designed a student and teacher survey to measure the impact of these snacks on the school. This meant collecting data on whether the snacks leave a mess, whether they are easy to pass out to all the homerooms, and whether they positively affect students who eat one.

What solution was implemented?

- We brainstormed snacks using our data to see what kind of snacks students would like best

- We looked at the budget and decided to serve snacks twice a week during the homeroom period

- We developed teacher and student surveys to assess reactions to the snack program

- We counted the number of students in each advisory, packaged up enough snacks for each class, and distributed snacks and surveys to the homerooms.

- We analyzed feedback about round 1 of the pilot and made adjustments for round 2

What changed as a result?

- We modified the pilot and now have twice-weekly snack pickups during homeroom with snacks of the students' choosing

- The principal included the program into next year's operating budget

- The school is committed to developing an after school meal program based on student feedback from the surveys

In the pilot, the team learned that most students and teachers appreciated the snacks provided and that handing out snacks during class helps build a sense of community and care within the school. (This last finding was counterintuitive to what the adults had initially worried about—that decentralizing food distribution in space and time would threaten the sense of community, not create it. It’s one example of dozens throughout the project that demonstrated the power of the YPAR model: students are experts, not research assistants.)

During Year 2, students again had the opportunity to share their work to a national audience. They shared the results of their snack program and the wider food equity initiative in a Policy Talk at the Association for Education Finance and Policy (AEFP) Conference in Baltimore. They presented again in April at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Conference in Philadelphia, once again as part of the Youth Teams in Education Research program. They were the only team to win the YTER award both years. At the conferences, the team discussed their research and design of the snack program – including how they distributed nearly 10,000 snacks to 80 different homeroom classes –the data they collected, how they adapted the pilot based on initial feedback, and what they have learned through design thinking more broadly.

Student Reflections

It was very informative. I got to learn the motives of a lot of different schools and researchers. They put the event on for us so that we can show that we as students are empowered in our own educational system. It was nice to see other students’ views on their schools and what they felt needed to change.

The Collaborative’s Role in Youth Participatory Action Research

For many, Youth Participatory Action Research is a paradigm shift. Scholars who are traditionally valued for their deep content knowledge, long-held expertise, and ability to define and answer research questions are required to cede all the components of a research project to young people. At the same time, they must pledge to value, support, and enable the decisions the young people make, even if they are not what they themselves would have chosen. (As a clear example, the adults on the CHEC team had initially set as a goal that students receive nutritious food; the students determined that their goal was to have students physically and mentally nourished with food they wanted to eat...which meant that in addition to reinstating the cafeteria’s salad bar, the daytime snack program included Oreos and Doritos.)

Researcher Reflections

Our meetings with the students were fun and thought-provoking. We prompted the students to think about what they could do with information they already had and what additional information they would need to come up with solutions that would serve the student body and increase cafeteria participation. Meanwhile the Collaborative spent a lot of time listening to the students talk about their experience at the school and what they heard from other students. One of the most important aspects of supporting this participant-research project is ensuring that we are always elevating student voices and perspectives from the DC community. It is vital that these students, who often have decisions made for them and are not listened to in academic spaces, feel that they have agency over how their school operates and meets their needs.

As the team advisors, the questions we most often fielded from other researchers and education stakeholders were not about food equity, but rather the YPAR process. How did we, as the supposed scholars and experts, implement the YPAR model and build trust with CHEC students and teachers? Our answer: embrace the model and all that comes with it. The point is to develop students’ skills and self-efficacy—this takes way more time than the traditional research model. Understand that lived experience is expertise. Cheerfully view challenging aspects of the model as opportunities. Stand back, stay in your lane, and allow for exploration and self-discovery. Bring snacks.

And most of all: facilitate, guide, and build students’ inquiry skills at all stages of the research process, not just the standard entry points. Students are more than data sources or research assistants, more than members of the research team, but rather its leaders and drivers.

Project Identification and Research Questions | |

Students:

| The Collaborative:

|

Data Collection | |

Students:

| The Collaborative:

|

Data Analysis and Drawing Conclusions from Data | |

Students:

| The Collaborative:

|

Making Decisions, Presenting Findings, and Taking Action | |

Students:

| The Collaborative:

|

What’s Next

For the 2024-2025 school year, we are engaging with a new team of food equity students, which includes 2 students returning from last year and 8 new students. We will seek more opportunities to strengthen our research-practice partnership and continue guiding the students in their research. As of now, the students are interested in sustaining their snack program and serving after-school meals for those who stay at school late. They are eager to engage with administrators and others in the DC Public Schools community to improve the experiences of their peers across the city.

By sharing the students’ work, we hope to highlight the importance of equipping youth with the tools they need to address issues they see in their community and share how the DC Education Research Collaborative supports the education research ecosystem across the District.

Stay tuned!